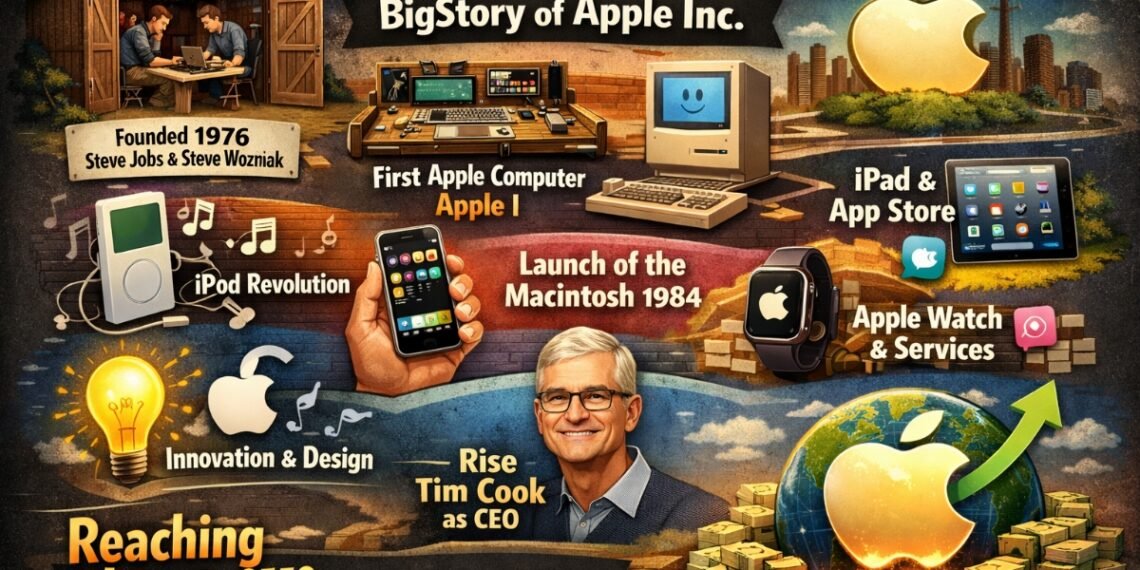

It started with two Steves, a soldering iron, and a dream too big for a garage to contain. Apple Inc.’s journey from a scrappy startup to a $3 trillion empire is the greatest business story ever told — a saga of genius, heartbreak, exile, triumph, and transformation that reshaped the world as we know it.

Opening Hook

Imagine it’s January 9, 2007. You’re standing inside the Moscone Center in San Francisco. The air is electric. Thousands of people are crammed inside, tech journalists and true believers alike, whispering in anticipation. Then a man in a black turtleneck walks onto the stage, a slight smile curling at the corner of his mouth.

“Every once in a while,” he begins, his voice low and deliberate, “a revolutionary product comes along that changes everything.”

He pauses. The room holds its breath.

“Today, Apple is going to reinvent the phone.”

What followed in the next sixty minutes would not merely launch a product. It would crack the world open and pour an entirely new one inside. The smartphone era was born. The internet became personal. The planet became connected in ways no one had fully imagined. And Apple — a company that had once, just a decade earlier, been ninety days from bankruptcy — stood at the center of it all.

But to understand how Apple got to that moment, you have to go back to the very beginning. Back to a suburb in Silicon Valley. Back to a garage. Back to two young men who believed, with almost irrational certainty, that ordinary people deserved extraordinary technology.

Chapter 1: The Garage Beginning (1976)

In the spring of 1976, the most important company in technology history did not yet exist. In its place was just a friendship — odd, combustible, and ultimately world-altering — between two young men who couldn’t have been more different from each other.

Steve Wozniak was an engineering prodigy. Quiet, gentle, and obsessed with circuits, “Woz” could look at a diagram and see solutions where others saw only problems. He was the kind of person who built things not for money or fame, but simply because he loved building things. His greatest joy was elegant engineering — doing more with less, solving complex problems through beautifully simple design.

Steve Jobs was something else entirely. He was restless, intense, and possessed of a vision so fierce it bordered on the delusional. He didn’t understand circuits the way Woz did, but he understood something more important: he understood people. He understood desire. He could look at a piece of technology and immediately sense what it needed to be to make someone fall in love with it.

Wozniak had designed a personal computer — the kind of machine that, in 1976, was the exclusive province of hobbyists who bought kits and spent weeks assembling their own systems. But Woz’s machine was different. It was fully assembled, already functional. Jobs took one look at it and saw not a hobbyist toy but a commercial product. He convinced Woz to sell it.

On April 1, 1976 — April Fool’s Day, as if the universe were winking — Steve Jobs, Steve Wozniak, and their older partner Ronald Wayne signed the papers that created Apple Computer Company. Wayne, nervous about liability, sold his 10% stake back to the other two for $800. It is perhaps the most expensive decision in business history.

The “garage” where Apple was born belongs to Jobs’s parents in Los Altos, California. The mythology of this garage — humble, suburban, impossibly ordinary — has been burnished over decades into something almost sacred. In truth, much of the early work happened in bedrooms and at kitchen tables. But the garage was real enough, and more importantly, what it represented was real: the idea that world-changing technology could be born not in a corporate laboratory or a university research center, but in the mundane domesticity of middle-class American life.

The Apple I sold for $666.66. They sold 200 units. It was, by any measure, a modest beginning. But then came the Apple II.

Chapter 2: Early Success and the Macintosh Revolution

The Apple II, launched in 1977, was a different beast entirely. Where the Apple I was a bare circuit board for hobbyists, the Apple II was a complete, polished computer for everyone. It had a keyboard. It had color graphics — a genuine novelty for the era. It had a clean, user-friendly design that reflected Jobs’s obsession with how things look and feel, not just how they work. And it came in an elegant, injection-molded plastic case that Jobs personally insisted upon when every engineer told him it was unnecessary.

The Apple II became one of the best-selling personal computers of its era. By the early 1980s, Apple was one of the fastest-growing companies in American history. When the company went public in December 1980, it generated more capital than any IPO since Ford Motor Company in 1956. Jobs, just twenty-five years old, became worth more than $200 million overnight.

But Jobs’s ambitions were not sated by success. They were inflamed by it.

In 1979, Jobs visited Xerox’s legendary research center, Xerox PARC, and saw something that would change everything: a graphical user interface. Instead of typing text commands into a black screen, users could click on icons with a device called a mouse. Pictures and windows appeared on screen. It was intuitive. It was human. Jobs was almost physically agitated by what he saw.

“Why isn’t Xerox doing something with this?” he demanded of his team afterward. “This is the computer of the future.”

Xerox, famously and tragically, did not see what Jobs saw. Apple did. The result was the Macintosh.

Launched on January 24, 1984, the Macintosh was introduced to the world through one of the most celebrated advertisements in history — a sixty-second television spot directed by Ridley Scott and aired during the Super Bowl. In it, a lone woman hurls a hammer through a screen displaying a totalitarian figure addressing gray masses. The message was unmistakable: IBM and its boring, conformist computing world was Big Brother. Apple — young, creative, alive — was freedom.

The Mac itself was a revelation. It was the first mass-market personal computer to make the graphical interface mainstream. It changed how people thought about computers — not as tools for technologists, but as creative instruments for anyone. Writers, designers, musicians, teachers — the Mac opened a door to computing that had previously been shut to most of humanity.

But behind the scenes, the story was far less triumphant.

Chapter 3: Power Struggles and Steve Jobs Leaving Apple

The early 1980s at Apple were not merely a chapter in business history. They were a Shakespearean drama playing out in conference rooms and parking lots across Cupertino.

Jobs was brilliant, but he was also difficult to the point of chaos. He terrorized engineers, publicly humiliated employees who failed to meet his standards, and made decisions with a certainty that often crossed the line from confidence into arrogance. He was also losing influence. The Apple II was Apple’s cash cow, and Jobs barely acknowledged it. He was consumed by the Mac.

In 1983, searching for an experienced executive to manage Apple’s growth, Jobs made a decision he would come to call the worst mistake of his life. He recruited John Sculley — the polished, Harvard-educated president of PepsiCo — with what became one of the most famous recruiting pitches in Silicon Valley history: “Do you want to spend the rest of your life selling sugared water, or do you want a chance to change the world?”

Sculley took the job. For a time, the two men were close. But as Apple’s fortunes fluctuated and Jobs’s behavior grew increasingly erratic, the relationship collapsed. The Mac’s initial sales surge faded. The board of directors, already weary of Jobs’s management style, sided with Sculley. In May 1985, Jobs was stripped of his management responsibilities. He was pushed out of the company he had founded.

On September 17, 1985, Steve Jobs resigned from Apple. He walked out of the building he had built. He was thirty years old.

The story of what Jobs did next — founding NeXT Computer, buying a struggling animation studio called Pixar, learning failure and patience and leadership in entirely new ways — is itself a remarkable saga. But it is also prologue. Because the more important story, for now, is what happened to Apple after he left.

Chapter 4: Apple’s Decline and Near Bankruptcy

Without Jobs, Apple became something he would have despised: ordinary.

Throughout the late 1980s and early 1990s, Apple stumbled through a series of uninspired products, confusing strategies, and leadership upheavals. The company launched a dizzying array of products under Sculley — printers, cameras, a personal digital assistant called the Newton — with little coherent vision binding them together. There were too many Mac models, too many versions, too much complexity. The elegance that had defined Apple under Jobs gave way to corporate bloat.

Meanwhile, Microsoft was eating Apple’s lunch. Windows 95 brought a graphical interface to the mass market running on cheap, generic hardware that anyone could manufacture. Apple’s hardware was proprietary, expensive, and — increasingly — perceived as a luxury for designers and eccentrics rather than a serious platform for everyday computing. Market share collapsed. Sculley was replaced by Michael Spindler, who was replaced by Gil Amelio.

By 1996, Apple was burning through cash at an almost incomprehensible rate. The operating system that powered the Macintosh was aging and deeply flawed. Several attempts to build a new operating system had failed spectacularly. The company needed a modern OS, and it needed one soon.

In December 1996, Apple announced it would acquire NeXT Computer — Jobs’s company — for $429 million. Ostensibly, Apple was buying NeXT for its advanced operating system technology. In reality, whether Apple’s board fully understood it or not, they were buying back Steve Jobs.

By the time Gil Amelio gave a disastrous, rambling keynote at the Macworld Expo in January 1997, Apple’s stock had fallen to around $3 per share. Time magazine ran a story questioning whether Apple would survive. Michael Dell was asked what he would do if he ran Apple. His answer was brisk and brutal: “I’d shut it down and give the money back to the shareholders.”

Apple was, as Jobs himself later put it, “90 days from bankruptcy.”

Chapter 5: Steve Jobs Returns — The Greatest Comeback

The board of directors finally ousted Amelio in July 1997. Jobs, initially serving as an informal adviser, was named interim CEO. He added the word “interim” to his badge and wore it with something between irony and warning. Within weeks, it was clear that whatever the badge said, Jobs was back. He was running things.

What Jobs did in the following months is one of the most dazzling acts of corporate turnaround in business history. He didn’t tinker at the edges. He dismantled the machine and rebuilt it from the center out.

First, he canceled 70% of Apple’s product lines — the printers, the servers, the Newton, the bewildering maze of Mac models — cutting the lineup down to just four computers: a consumer desktop, a professional desktop, a consumer laptop, a professional laptop. Simple. Focused. Ruthless.

Next, he did something that shocked both the technology industry and Apple’s own loyal customers: he announced a partnership with Microsoft. Bill Gates’s face appeared on the enormous screen at Macworld Boston via satellite, instantly provoking boos from the crowd. But Jobs had secured a $150 million investment from Microsoft and a commitment to continue developing Microsoft Office for Mac. It was pragmatism triumphing over pride. Apple needed the partnership to survive, and Jobs knew it.

He also brought in a new design philosophy, hiring a young British designer named Jony Ive who had been quietly working at Apple and had never quite found an executive who shared his vision. Under Jobs, Ive would become the most important industrial designer in technology history. Their partnership — one man’s taste, another man’s craft — would define Apple’s aesthetic for the next two decades.

Chapter 6: The iMac, iPod, and Apple’s Reinvention

The iMac arrived in August 1998 looking like nothing anyone had seen on a desk before. It was a computer encased in a translucent, candy-colored shell — bone white and Bondi blue — curvy and inviting where other computers were beige and forbidding. The advertising was simple: “Hello (again).” A nod to the original Mac’s debut, and a declaration that Apple was back.

The iMac sold 800,000 units in its first 139 days. It was the best-selling computer in America. Apple returned to profitability. The press, which had spent two years writing Apple’s obituary, began writing its resurrection instead.

In 2001, Apple opened its first retail stores — a decision that most retail analysts predicted would be a catastrophic failure. Within three years, Apple Stores were generating more revenue per square foot than any retail operation in the world, including Tiffany & Co. Jobs had understood, before anyone else, that selling technology required an experience, not just a transaction.

Also in 2001 came the iPod. The portable music player market was already crowded with clunky devices that held dozens of songs. The iPod held 1,000 songs. Its scroll wheel was so intuitively satisfying to use that people played with it just for the pleasure of it. Jobs’s marketing was characteristically brilliant: “1,000 songs in your pocket.” Not a specification. A feeling. A lifestyle. A promise.

The iPod, paired with the iTunes Music Store launched in 2003, didn’t merely sell music players. It transformed the music industry. For 99 cents a song, Apple offered a legal, elegant alternative to piracy at a moment when the music industry was hemorrhaging revenue to Napster and its descendants. The record labels, desperate for a solution, climbed into bed with Apple. Within a year, the iTunes Store was the dominant legal online music retailer in the world.

Apple’s ecosystem — the idea that devices, software, and services would work together seamlessly in a walled garden of Apple’s own design — was beginning to take shape.

Chapter 7: The iPhone — The Product That Changed the World

There is a moment, early in the development of what would become the iPhone, where Jobs turned to his engineering team and said something that captured everything about how his mind worked. They had been developing a tablet — a touchscreen device that could replace the laptop for casual use. But Jobs kept looking at the prototype and thinking about phones.

“The most important product I’ll ever make in my life,” he reportedly told team members, “is the phone that every person on earth carries in their pocket.”

The development of the iPhone was shrouded in legendary secrecy. Engineers working on different components didn’t know what the others were building. When Jobs finally unveiled it at Macworld in January 2007, it was a genuine surprise — not just to the world, but to most of Apple’s own workforce.

What Jobs announced that day was, as he described it, three products in one: an iPod with touch controls, a revolutionary mobile phone, and a breakthrough internet communications device. The crowd laughed when he repeated the list, not quite understanding. Then he dropped the punchline: “These are not three separate devices. This is one device.”

The iPhone shipped in June 2007. People camped outside Apple Stores for days to be among the first to own one. The mobile phone industry — dominated by Nokia, Motorola, and BlackBerry — was caught flatfooted. BlackBerry’s co-CEO Jim Balsillie reportedly said he wasn’t losing sleep over the iPhone. Nokia’s executives passed around one of the first models in a meeting and agreed it was nothing they needed to worry about.

Within five years, BlackBerry was irrelevant. Nokia had sold its phone division. The entire architecture of mobile computing — the App Store, the mobile internet, the smartphone economy — had been remade around the model Apple introduced.

The App Store, launched in 2008, was perhaps even more transformative than the iPhone hardware itself. By creating a marketplace for software that ran on the iPhone, Apple didn’t just sell a device. It created a platform. Startups like Instagram, Uber, and Airbnb were built on the smartphone revolution the iPhone ignited. Billions of dollars in new wealth were created. The app economy, by the mid-2020s, would generate more than a trillion dollars in annual revenue worldwide.

By 2011, Apple had surpassed ExxonMobil to become the most valuable company in the world. The company that had been 90 days from bankruptcy in 1997 was now worth hundreds of billions of dollars.

But the man who had built it was dying.

Chapter 8: The Death of Steve Jobs — The End of an Era

Steve Jobs was diagnosed with a rare form of pancreatic cancer in 2003. He delayed surgery for nine months — a decision that some doctors believe significantly affected his prognosis. He underwent surgery in 2004. For a time, he appeared to recover.

But the cancer returned. By 2009, Jobs was visibly thin at public appearances. He took a medical leave of absence, then returned. He appeared at the iPad 2 launch in March 2011 — gaunt, but electrifying. He announced iCloud at WWDC in June, standing on stage with characteristic precision and passion.

On August 24, 2011, Steve Jobs resigned as Apple’s CEO, naming Tim Cook as his successor. His resignation letter was brief: “I have always said if there ever came a day when I could no longer meet my duties and expectations as Apple’s CEO, I would be the first to let you know. Unfortunately, that day has come.”

On October 5, 2011, Steve Jobs died at his home in Palo Alto, California. He was fifty-six years old. The world responded as if it had lost a head of state. Flowers and handwritten notes appeared outside Apple Stores in cities across the globe. World leaders offered condolences. Artists, musicians, and writers tried to describe what had been lost.

What had been lost was singular and irreplaceable: the most consequential product visionary of the modern age. A man whose insistence on perfection, whose refusal to accept “good enough,” whose understanding that technology and art could and should coexist — had remade not just an industry but the texture of daily life for billions of people.

He had revolutionized personal computing, animated films, music distribution, and telecommunications. He had done it not once but multiple times. He had been exiled and had returned. He had come within weeks of failure and had rebuilt an empire.

And now he was gone. Apple had to figure out who it was without him.

Chapter 9: Tim Cook and the Rise to $3 Trillion

Tim Cook is not Steve Jobs. He has never pretended to be. And that, as it turns out, may be precisely why he was the right person to lead Apple after Jobs.

Where Jobs was intuitive and mercurial, Cook is methodical and disciplined. Where Jobs chased the product above all else, Cook has an extraordinary gift for operations — for the supply chains, the manufacturing relationships, the financial engineering that turns brilliant products into global businesses at scale.

The skeptics were loud in the months after Jobs’s death. Apple without Jobs, they argued, would lose its creative edge. It would become just another tech company — competent, profitable, but no longer transformative. The magic, they said, would die with its creator.

The skeptics were wrong.

Under Cook, Apple launched the iPhone 5, then 6, then 6 Plus — breaking into the large-screen smartphone market that Samsung had dominated. The Apple Watch, launched in 2015, created a new product category and became the best-selling wearable device in the world within its first year. Apple Silicon — custom chips beginning with the M1 in 2020 — delivered performance benchmarks that left the PC industry stunned.

Cook also made Apple into something Jobs never quite had: a company with a social conscience. Cook came out publicly as gay in 2014, making him the first openly gay CEO of a Fortune 500 company, and he used his platform to advocate for civil rights, environmental responsibility, and privacy. Apple committed to running entirely on renewable energy. Cook pushed back against government attempts to weaken iPhone encryption, arguing that user privacy was a fundamental human right.

On the financial side, the numbers became almost incomprehensible. Apple’s revenues surpassed $100 billion in a single quarter. In August 2018, Apple became the first U.S. company to achieve a market capitalization of $1 trillion. In August 2020 — amid a global pandemic — it crossed $2 trillion. In January 2022, Apple became the first company in history to achieve a market capitalization of $3 trillion.

Three trillion dollars. The GDP of France. The combined market value of Walmart, ExxonMobil, and JPMorgan Chase. Numbers that stagger the imagination.

From $666.66 per computer in a California garage. To $3 trillion.

Chapter 10: Apple Today — The Most Powerful Company in the World

Today, Apple is not merely a technology company. It is a civilization unto itself.

More than two billion Apple devices are active worldwide. The Apple App Store hosts nearly two million apps and has distributed more than $320 billion in payments to developers since its launch. Apple Music has more than 100 million subscribers. Apple TV+ has won Emmy Awards and Academy Awards. Apple Pay processes hundreds of billions of dollars in transactions annually. Apple’s services division alone generates more revenue annually than most Fortune 500 companies.

The iPhone remains the company’s central product, but the ecosystem around it has grown into something far more vast and sticky than any single device. An iPhone user who also has an Apple Watch, AirPods, a MacBook, and an iPad has entered a gravitational field from which it is technically possible, but psychologically difficult, to escape. The devices talk to each other. They share data effortlessly. They assume a continuity of experience that no competing ecosystem has yet matched.

The Apple Watch has evolved from a luxury smartwatch into a genuine health device — capable of detecting irregular heart rhythms, measuring blood oxygen levels, and detecting falls. With each iteration, it moves closer to something Jobs once imagined but didn’t live to see: a device that monitors and protects your health in real time, worn on your wrist.

Apple Vision Pro, unveiled in 2023 and launched in early 2024, introduced the company’s first entirely new product platform since the Apple Watch — a spatial computing headset that layers digital information onto the physical world. Whether Vision Pro is the iPod of spatial computing — an early, imperfect prototype of something that will eventually reshape everything — remains to be seen. But the question itself is a tribute to Apple’s continued ambition.

Chapter 11: Apple’s Legacy and Future

History will debate many things about Apple. Whether its closed ecosystem is a gift or a prison. Whether its market power amounts to monopoly. Whether its labor practices in overseas supply chains are consistent with its stated values. These are legitimate debates, and they matter.

But what history will not debate is this: Apple changed the world.

It changed the world in 1984, when the Macintosh made computing accessible to ordinary people. It changed the world in 2001, when the iPod made digital music a mass-market reality. It changed the world in 2007, when the iPhone collapsed the internet into a pocket-sized screen and put the sum of human knowledge within a thumb’s reach of every person on the planet. It changed the world in 2010, when the iPad created a new computing category that brought technology to people who had never used a laptop or desktop.

The future Apple is building is one in which artificial intelligence is woven into every device and experience. “Apple Intelligence,” unveiled in 2024, represents the company’s push into generative AI — integrating AI capabilities into Siri, Messages, Photos, and more, with a characteristic emphasis on doing it on-device to protect user privacy. It is a different approach from Google and Microsoft, who have raced to embed AI into cloud services. Whether Apple’s approach wins, loses, or reshapes the AI landscape in ways not yet foreseeable is the most interesting technology question of the late 2020s.

Conclusion: Why Apple’s Story Matters

On a warm afternoon in 1976, a young man in Los Altos, California, looked at a circuit board his friend had built and saw — with a clarity that defied logic and experience — a product. Not just a product. A company. Not just a company. A revolution.

That young man was twenty-one years old. He had no formal engineering training. He had dropped out of college. He was, by most conventional measures, unqualified to change the world.

He changed it anyway.

Apple’s story is, on its surface, a business story. It is about market capitalizations and product launches and competitive dynamics and quarterly earnings. But underneath all of that — underneath the silicon and the software and the stock price — it is a story about something more fundamental.

It is a story about what happens when human beings refuse to accept the world as it is. When they look at a complicated, ugly, intimidating machine and ask: what if this could be beautiful? What if this could be simple? What if this could be for everyone?

It is a story about failure. About the kind of failure that looks final, that reads like an ending, but turns out to be the necessary prelude to something extraordinary.

It is a story about what one person’s vision can do — and about what happens when that vision is institutionalized so deeply that it outlives the person who had it.

From a garage to three trillion dollars. From two Steves with a circuit board to the most valuable company in human history. From a machine for hobbyists to a device carried by billions. From a company that almost died to one that became, for a remarkable stretch of years, the most important enterprise on the planet.

Apple’s story matters because it is not just Apple’s story. It is the story of what is possible when imagination is taken seriously. When design is treated as essential rather than cosmetic. When the question “what could this be?” is given the same weight as “what is this?”

It is the story of the garage that held the future, and the two young men who let it out.

So, this was the BigStory of Apple Inc., the company that began in a small garage and went on to redefine technology, business, and culture across the world. At BigStories, our goal is to bring you the journeys behind the companies and ideas that shaped the modern era. If you enjoyed reading this story, consider sharing it with others who use Apple products every day, and explore more BigStories that reveal how today’s world was truly built.

Published on BigStories.net | Category: Business & Technology