Yahoo’s Complete History: From Stanford Dorm to Internet Giant — and What Went Wrong

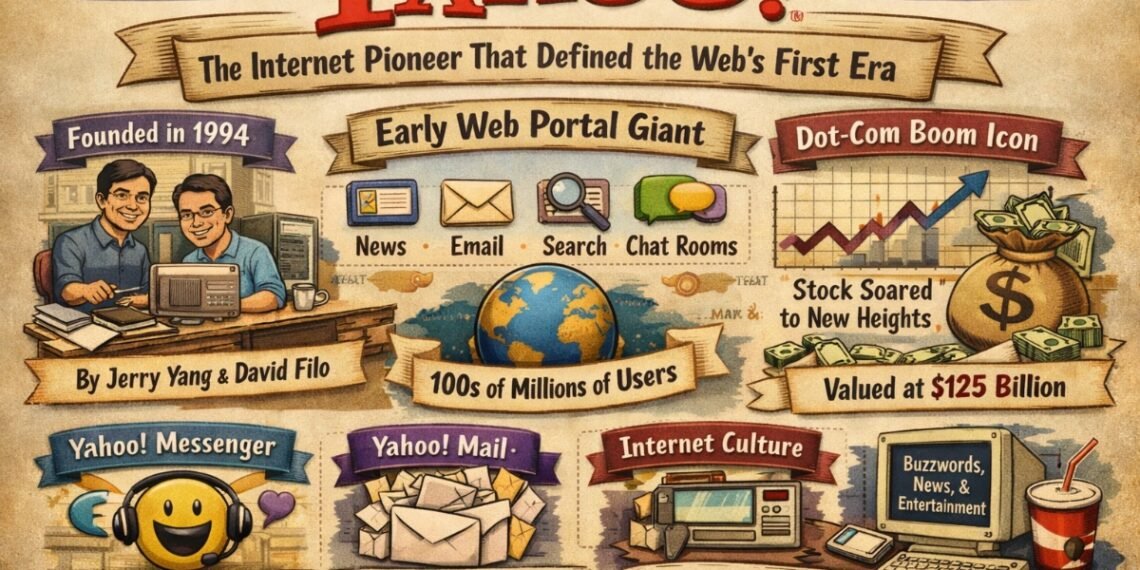

Before Google became a verb. Before Facebook connected billions. Before the smartphone made the internet something you carried in your pocket — there was Yahoo. A purple logo. A yodel. And a directory of links that felt, in 1994, like a map to an entirely new universe.

For millions of people around the world, Yahoo wasn’t just a website. It was the website. It was the place you went every morning — your email, your news, your weather, your stocks, all in one place. Yahoo was the internet’s front door, and for nearly a decade, almost everyone knocked on it.

The story of Yahoo is one of the most fascinating — and instructive — in the history of technology. It’s a story of two graduate students who built something extraordinary from a hobby. Of a company that rode the dot-com wave to dizzying heights, then watched rivals outmaneuver it at nearly every turn. Of missed opportunities so enormous they still sting decades later.

But it’s also a story of genuine, lasting impact. Yahoo didn’t just survive the early web — it shaped it. And understanding how, and why it eventually faltered, tells us something profound about innovation, leadership, and the relentless pace of change in the digital age.

The Birth of Yahoo: Founders, Idea, and Early Days

The origin story of Yahoo begins not in a gleaming Silicon Valley office, but in a cramped trailer on the Stanford University campus in the winter of 1994. Jerry Yang and David Filo, two doctoral students in electrical engineering, had a problem that millions of early internet users shared: the web was growing at a staggering pace, and nobody could find anything on it.

Their solution was elegantly simple. They started keeping a personal list of their favorite websites, organized into categories. What began as a way to procrastinate on their dissertations quickly became something much bigger. As their list grew into the thousands, they noticed traffic to their site exploding. People were desperate for exactly this — a human-curated guide to the internet.

By January 1994, “Jerry and David’s Guide to the World Wide Web” had outgrown its original name. The two searched through a dictionary for something catchier and landed on “Yahoo,” which stood for “Yet Another Hierarchical Officious Oracle” — though Yang and Filo have always admitted they chose it partly because they liked the word’s irreverent energy.

By March 1995, Yahoo had incorporated. Sequoia Capital invested $2 million — a bet that would return thousands of times over. The company set up offices in Santa Clara, California, and hired its first CEO, Tim Koogle, a seasoned executive who helped professionalize the scrappy startup. Within months, Yahoo was no longer a graduate school project. It was a company, and it was about to change everything.

Jerry Yang and David Filo: The Minds Behind Yahoo

Jerry Yang was born in Taipei, Taiwan, in 1968. He immigrated to the United States at age ten, speaking almost no English. By his twenties, he was a Stanford Ph.D. student with a gift for seeing patterns in complexity — a skill that would prove essential in the chaotic early web.

David Filo, a Louisiana native, was the quieter counterpart. Where Yang would become the public face of Yahoo, Filo was the technical backbone, the engineer obsessively refining the backend infrastructure that kept the site running as traffic surged. Those who worked with both described a complementary dynamic: Yang as the visionary communicator, Filo as the architect who made the vision real.

What made them unusual as founders was their evident lack of ego about the project’s origins. They genuinely seemed surprised — delighted, even — that their personal bookmark list had become a cultural phenomenon. That humility served them well in the early years but may have also contributed to a certain reluctance to make the hard, aggressive decisions that would define the company’s later struggles.

Yang would later serve as Yahoo’s CEO from 2007 to 2009 during one of the company’s most turbulent periods, turning down Microsoft’s $44.6 billion acquisition offer — a decision that remains one of the most debated in Silicon Valley history. Filo stayed largely out of the spotlight, remaining as a technical advisor for years. Both men became billionaires, but the weight of Yahoo’s eventual decline would hang over their legacy in complex ways.

How Yahoo Organized the Early Internet

To appreciate what Yahoo accomplished, you have to understand how genuinely chaotic the early web was. In 1994, there were roughly 3,000 websites. By 1996, there were over 600,000. By 1998, millions. And crucially, there was no reliable way to find what you were looking for.

Yahoo’s directory was not a search engine in the modern sense. It was a taxonomy — a hand-curated hierarchy of categories and subcategories, maintained by human editors who reviewed and classified each site. You might navigate: Computers > Software > Databases > MySQL. Or Entertainment > Music > Jazz > Contemporary. It was, in essence, a library catalog for the internet.

This approach had a profound advantage in the mid-1990s: it was trustworthy. A human had looked at every site in the directory and decided it belonged there. In an era before spam, SEO manipulation, and content farms, that editorial judgment had genuine value.

Yahoo’s editors — eventually numbering in the hundreds — became the unsung heroes of the early web, making judgment calls about categorization that shaped how millions of people understood and navigated online space. Getting listed in the Yahoo Directory was a major event for any website, capable of driving significant traffic overnight.

It was a fundamentally different philosophy from what would later emerge from Google: instead of an algorithm that tried to read the web’s mind, Yahoo offered human intelligence and organizational structure. For a brief, important window, that was exactly what the world needed.

Yahoo Directory: The Original Gateway to the Web

The Yahoo Directory was, for several years in the mid-1990s, the single most important navigational tool on the internet. It was organized across broad categories — Arts, Business, Computers, Education, Entertainment, Government, Health, News, Recreation, Science, Social Science, and Society & Culture — each of which branched into increasingly specific subcategories.

What made the Directory remarkable was not just its comprehensiveness but its personality. The editors had latitude to write descriptions with wit and taste. Yahoo felt human in a way that later algorithmic systems never quite replicated.

For businesses, being listed in the Yahoo Directory was essential. Yahoo introduced a Business Express service in 1996 that charged a fee for priority review, generating significant revenue while also accelerating the directory’s growth. Entire consultancies emerged whose sole purpose was helping companies optimize their Yahoo Directory listings.

The Directory eventually peaked at covering millions of sites, but its hand-curated model became its fatal flaw as the web scaled into the billions of pages. No team of human editors could keep pace. By the early 2000s, Yahoo had already begun shifting emphasis toward algorithmic search, and the Directory was slowly marginalized. Yahoo officially shut it down in December 2014, closing a chapter in internet history that younger users had largely forgotten existed. It was a quiet ending for something that had once been the internet’s indispensable compass.

Yahoo’s Explosive Growth in the 1990s

The numbers tell a story that still stagger. In 1995, Yahoo was handling roughly 1 million page views per day. By 1997, that figure had climbed to 65 million. By 1999, it was approaching a billion daily page views. No media company in history had grown an audience this fast.

Several factors drove this extraordinary expansion. First, the sheer novelty of the internet itself: Yahoo benefited enormously from being in the right place at the right moment when mainstream America came online. Second, Yahoo’s strategy of building a “portal” — a one-stop destination for everything a user might want online — proved brilliantly effective. Email, news, weather, sports scores, stock quotes, classified ads, maps: Yahoo assembled them all under one roof.

Third, Yahoo was extraordinarily effective at marketing. The famous yodel in its commercials became one of the most recognized audio signatures of the decade. The purple-and-yellow brand was everywhere — on television, billboards, buses, and eventually, in 1999, on an NFL stadium (now known as Levi’s Stadium in Santa Clara, though the naming deal was with the San Francisco 49ers predecessor arrangement).

Yahoo also built strong international operations early, launching country-specific versions across Europe and Asia. Yahoo Japan, launched in partnership with SoftBank in 1996, became one of the most successful Yahoo ventures and remains a significant business today, entirely separate from the American parent company after the corporate restructures of the 2010s.

Yahoo IPO and Dot-Com Boom Success

On April 12, 1996, Yahoo went public. The IPO priced at $13 per share; by end of day, the stock had nearly doubled to $33. Yahoo raised $33.8 million. The company was valued at roughly $850 million — an extraordinary figure for a two-year-old company with modest revenues.

But even that number would look conservative within a few years. As the dot-com boom accelerated through 1998 and 1999, Yahoo’s stock entered the stratosphere. At its peak in January 2000, Yahoo’s market capitalization touched $125 billion. Jerry Yang and David Filo were paper billionaires many times over. Tim Koogle was celebrated as one of the great business leaders of the age.

Yahoo used its soaring stock price as a currency for acquisitions, snapping up dozens of companies during the boom years. The company diversified aggressively, adding services, content, and capabilities at a pace that sometimes outstripped its ability to integrate them.

The advertising model powering all this was still relatively primitive — banner ads, primarily — but in an era when companies were spending freely to establish their online presence, Yahoo’s enormous traffic base made it the most valuable advertising platform on the web. Revenues grew from $21 million in 1997 to $1.1 billion in 2000.

When the bubble burst in 2000 and 2001, Yahoo was among the hardest hit. Its stock fell more than 97% from peak to trough. But unlike hundreds of dot-com casualties, Yahoo survived. The core business was real. The audience was real. And the challenge of rebuilding would define the next decade.

Yahoo Mail: Revolutionizing Communication

When Yahoo acquired RocketMail in October 1997 and relaunched it as Yahoo Mail, it transformed the relationship between ordinary people and email. Before web-based email services, email required a desktop client, an ISP account, and a degree of technical knowledge that kept it the domain of students, academics, and tech workers.

Yahoo Mail changed that entirely. Suddenly, anyone with internet access — at a library, a school, a cybercafé — could have a free email address. The psychological impact was profound: email became personal rather than institutional. Your Yahoo address was yours, not dependent on your employer or school.

Yahoo Mail grew with breathtaking speed. By 1998 it had tens of millions of users. By 2004, it had over 100 million. At one point in the 2000s, Yahoo Mail was the single most-used email service on the planet, a distinction it held until Google’s Gmail — launched in 2004 with a revolutionary 1-gigabyte storage offer — began its ascent.

Yahoo Mail’s trajectory mirrored the company’s broader arc: dominant, then complacent, then struggling to catch up with more innovative competitors. The product itself saw relatively slow improvement through the early 2000s, a stark contrast to Gmail’s relentless iteration. By the time Yahoo made serious upgrades to its interface and features, Google had already captured the imagination of the users who mattered most.

Yahoo Homepage: The Internet’s Front Door

For a significant portion of the internet-connected world in the late 1990s and early 2000s, opening a web browser meant seeing Yahoo. Not because of any technical default, but because millions of users had simply chosen it — set it as their homepage, typed it from muscle memory, returned to it out of habit and genuine affection.

The Yahoo homepage was a masterwork of information architecture for its time. Packed with links, updated constantly, it managed to feel manageable rather than overwhelming. Your email. Today’s news. Sports scores. TV listings. Stock quotes. Weather. Horoscopes. A search box. All in one glance.

This concept — the portal — was Yahoo’s most important strategic innovation. The logic was compelling: if users came to Yahoo first and could find everything they needed without leaving, Yahoo would own their attention, and attention was the currency of the web economy.

For several years, it worked magnificently. But the portal strategy carried a hidden vulnerability: it required Yahoo to be excellent at everything. Email, search, news, entertainment — each product had to be good enough to retain users. When Google arrived with a better search engine, users began leaving Yahoo for searches. And search, it turned out, was the hinge on which everything else turned.

The Yahoo homepage also reflected the company’s evolving identity challenges. As Yahoo tried to be all things to all people, the homepage became increasingly cluttered, struggling to balance information density with usability. By the mid-2000s, what had once felt comprehensive began to feel overwhelming and dated.

Yahoo Search and Its Competition with Google

Yahoo’s relationship with search is one of the great tragic ironies of tech history. Not only did Yahoo fail to out-execute Google in search — Yahoo actually had the opportunity to own Google, and passed on it.

In Yahoo’s early years, search was a secondary concern. The Directory was the product; search was a utility. Yahoo initially used third-party search technology from open-source systems and later from Inktomi, which it acquired in 2002. It also briefly used Google’s technology to power its search results — an arrangement that gave Google enormous credibility and traffic while Yahoo focused on portal features.

In 2002, Yahoo made what seemed like a decisive move, acquiring Inktomi for $235 million and later acquiring Overture Services (the company that pioneered paid search advertising) for $1.63 billion in 2003. For a brief moment in 2004, after integrating this technology into its own “Yahoo Search,” the company appeared to be mounting a genuine challenge to Google.

But Google was moving faster. Its PageRank algorithm produced better results. Its clean, uncluttered interface resonated with users who found portals overwhelming. Its AdWords system was generating revenue at a rate that shocked the industry. Yahoo’s search technology was solid — but not good enough to overcome Google’s head start and superior user experience.

By 2009, Yahoo had conceded the search war entirely, entering a deal to use Microsoft’s Bing technology to power its search results. It was a pragmatic business decision that nonetheless symbolized a profound capitulation. Yahoo, the company that had introduced much of the world to the internet, was no longer capable of independently answering the most basic question that web users ask: What am I looking for?

Major Yahoo Acquisitions: GeoCities, Tumblr, Flickr, Broadcast.com, and More

Yahoo made dozens of acquisitions over its lifetime, and they reveal both the company’s ambitions and its recurring struggles with integration and strategy.

GeoCities (1999, $3.57 billion): At the height of the dot-com boom, Yahoo paid a staggering price for GeoCities, the platform that had allowed millions of ordinary users to build their own free websites. GeoCities was, in its heyday, one of the most visited destinations on the web. But Yahoo struggled to monetize or meaningfully improve it. In 2009, Yahoo shut GeoCities down entirely — erasing a vast archive of early web culture that historians and archivists still mourn. The Internet Archive managed to preserve much of it, but the closure was widely criticized as both a business and cultural failure.

Broadcast.com (1999, $5.7 billion): The largest all-stock deal in internet history at the time, Yahoo’s acquisition of Mark Cuban’s Broadcast.com was supposed to establish Yahoo as the dominant force in internet video and audio streaming. Instead, it became a symbol of dot-com excess. The technology was ahead of the infrastructure required to make streaming viable at scale, and the business largely withered. Mark Cuban walked away with nearly a billion dollars in Yahoo stock, which he famously and cleverly hedged before the crash.

Flickr (2005, ~$22–25 million): This acquisition was, arguably, Yahoo’s most genuinely prescient. Flickr, founded by Stewart Butterfield and Caterina Fake, was a revolutionary photo-sharing platform that pioneered many features — tags, communities, APIs — that would define Web 2.0. The price was modest. But Yahoo’s management of Flickr became a cautionary tale in its own right. Rather than accelerating Flickr’s growth, Yahoo imposed its own bureaucratic processes, slowed development, and failed to respond to the threat posed by Facebook’s photo features. Flickr, which could have been Instagram before Instagram, was squandered.

Tumblr (2013, $1.1 billion): Marissa Mayer’s most high-profile acquisition was Tumblr, the blogging and microblogging platform beloved by creative communities. The price reflected genuine ambition: Mayer wanted Yahoo to be relevant to younger users. But Yahoo never found a viable advertising model for Tumblr’s unique community culture, and the platform continued to decline. Verizon eventually sold Tumblr to Automattic (the company behind WordPress) in 2019 for a reported $3 million — a loss of over $1 billion and one of the starkest write-downs in Silicon Valley history.

Yahoo’s Missed Opportunities: Google, Facebook, YouTube

If Yahoo’s acquisitions reveal strategic confusion, its missed opportunities reveal something even more striking: a company that repeatedly identified the future accurately, then declined to act.

Google (1998, ~$1 million): Larry Page and Sergey Brin approached Yahoo in 1998, seeking to sell their search technology for approximately $1 million. Yahoo passed. The founders then sought to sell to Excite for $750,000 — which also passed. Yahoo would later be valued at a fraction of what Google became. The company also passed on an opportunity to acquire Google in 2002, when Google’s asking price was reportedly $3 billion. Yahoo considered it too expensive.

Facebook (2006, $1 billion): In 2006, Yahoo offered to acquire Facebook for $1 billion. Mark Zuckerberg, then 22, turned it down — a decision that was widely mocked at the time but proved to be one of the most financially savvy moves in business history. Yahoo might have paid $1 billion for a company that would eventually reach a market capitalization exceeding $1 trillion.

Microsoft (2008, $44.6 billion): Perhaps the most consequential missed opportunity of all. Microsoft, under CEO Steve Ballmer, offered to acquire Yahoo for $44.6 billion — a 62% premium on Yahoo’s then-current stock price. Jerry Yang, serving as CEO at the time, rejected the offer. Shareholders were furious. Activist investors launched campaigns. The deal collapsed. Yahoo’s stock subsequently fell dramatically. The decision to reject Microsoft’s offer is widely regarded as one of the most damaging strategic errors in tech history, costing Yahoo shareholders tens of billions in value.

YouTube (2006): Yahoo was reportedly in discussions to acquire YouTube before Google swooped in with its $1.65 billion offer. Yahoo passed. Video would go on to be one of the most transformative forces in digital media.

Yahoo vs. Google: The Turning Point

The pivotal moment in the Yahoo-Google rivalry came not with a single dramatic event, but through an accumulation of choices — most of them made between 1998 and 2004.

When Yahoo decided to build a portal rather than focus relentlessly on search, it was making an entirely rational decision by the business logic of the era. Portals generated engagement, and engagement generated advertising revenue. Search was, in the late 1990s, seen as a commodity — a utility that every portal offered but that no portal particularly distinguished itself with.

Google saw it differently. Larry Page and Sergey Brin believed that search quality was everything — that if you could find what you were looking for faster and more accurately, users would prefer you, and that preference could be monetized. They were right, and their insight rewrote the economics of the internet.

By 2004, when Google went public, the comparison had become painful. Google’s IPO raised $1.67 billion at a valuation of $23 billion for a company with far fewer employees and products than Yahoo. Within a year, Google’s market cap had surpassed Yahoo’s. The student had outgrown the teacher. By 2012, Google’s revenues were more than five times Yahoo’s.

What Yahoo’s leaders failed to understand — or understood but couldn’t act on — is that on the internet, the best product wins. Not the most comprehensive product. Not the most familiar product. The best one. Google built the best search engine. Then the best advertising system. Then the best mobile operating system. Yahoo, meanwhile, tried to win by owning everything and excelled at very little.

Leadership Changes and Strategic Mistakes

Yahoo’s leadership history reads like a case study in strategic paralysis. Between 2000 and 2012, the company cycled through multiple CEOs, each facing the same fundamental challenge — how to rebuild Yahoo’s relevance in an internet increasingly dominated by Google — and none fully solving it.

Tim Koogle led the company through its founding era and the dot-com collapse before departing in 2001. Terry Semel, a veteran Hollywood executive recruited to bring media sophistication to Yahoo, served from 2001 to 2007. Semel brought discipline and professional management to Yahoo’s operations and presided over a genuine recovery period, but his failure to decisively invest in search technology and his eventual rejection of a Google acquisition attempt became defining shortcomings.

Jerry Yang’s return as CEO in 2007 was driven by a genuine desire to save the company he’d founded, but his tenure was defined by the Microsoft rejection saga. Carol Bartz, the blunt and experienced software executive who followed Yang in 2009, cut costs aggressively but couldn’t articulate a compelling strategic vision. She was fired in 2011.

Scott Thompson served briefly in 2012 before resigning amid a controversy about his academic credentials. Then came Marissa Mayer.

Mayer’s 2012 appointment generated genuine excitement. A former Google executive and one of tech’s most prominent executives, she brought star power and apparent strategic clarity. She improved Yahoo’s products, made important acquisitions, and stabilized the company’s culture. But the fundamental challenge remained: Yahoo’s core advertising business was in structural decline, squeezed between Google’s dominance in search advertising and Facebook’s rising power in social media advertising.

Mayer’s tenure ended in 2017 when Verizon’s acquisition closed, and she departed with a significant severance package while Yahoo’s fate passed into other hands.

Yahoo’s Role in Shaping Internet Culture

Beyond its products and business decisions, Yahoo played a profound and underappreciated role in shaping internet culture as we know it.

Yahoo Groups (launched in 2001 after acquiring eGroups) was one of the first large-scale online community platforms, hosting millions of interest communities ranging from gardening clubs to political organizations to rare disease support groups. For many users in the early 2000s, Yahoo Groups was their first experience of finding “their people” online. The service continued for nearly two decades before Yahoo finally shut it down in 2019, to the grief of communities that had maintained active discussions for years.

Yahoo Answers, launched in 2005, became a uniquely democratic knowledge platform — and, eventually, a beloved cultural artifact of internet absurdity. Its questions (famously exemplified by “How is babby formed?”) became internet memes, but beneath the humor was a genuinely important experiment in crowd-sourced knowledge. Yahoo Answers was shut down in 2021.

Yahoo’s early embrace of user-generated content, community features, and the democratization of web publishing helped establish norms that Web 2.0 platforms would later build upon. GeoCities, whatever Yahoo’s failure to preserve it, introduced an entire generation to the idea that anyone could have a presence on the web.

Yahoo also played a significant role in bringing the internet to developing markets, particularly through partnerships in Asia, establishing the template for localized internet portals that companies like Tencent and Baidu would later refine and dominate.

Yahoo Finance, Yahoo News, and Other Successful Products

Amid its broader struggles, Yahoo maintained a set of products that remained genuinely excellent — and some that continue to dominate their categories today.

Yahoo Finance is, by most measures, Yahoo’s most enduring success story. Launched in 1997, Yahoo Finance became the go-to destination for retail investors seeking stock quotes, financial news, earnings data, and portfolio tracking tools. At its peak, it attracted over 70 million monthly visitors. What’s remarkable is that Yahoo Finance has maintained this dominance even as other Yahoo properties faded. As of 2025, it remains one of the most visited financial information sites on the internet — a genuine jewel that survived the company’s tumultuous ownership changes largely intact.

Yahoo News similarly maintained a large audience through multiple ownership transitions, aggregating news from major outlets and presenting it to a broad general audience. While it never developed the editorial identity of a true news organization, its traffic remained substantial — a reflection of the enormous installed base of Yahoo users who continued visiting out of habit.

Yahoo Sports built a particularly loyal following, especially for fantasy sports. Yahoo Fantasy Football became one of the most popular fantasy sports platforms in the United States, building communities and annual rituals that proved remarkably sticky even as users migrated away from other Yahoo products.

Yahoo Messenger, launched in 1998, was one of the pioneering instant messaging services and had hundreds of millions of users at its peak. Like many Yahoo products, it was eventually unable to compete with newer messaging platforms and was shut down in 2018.

The Decline of Yahoo

Yahoo’s decline was neither sudden nor inevitable — it was the accumulation of a thousand decisions made too slowly, too cautiously, or simply incorrectly.

The structural problem was that Yahoo’s business depended on display advertising, and display advertising was being disrupted by the rise of search-based advertising (dominated by Google) and later social media advertising (dominated by Facebook). Yahoo was caught between two tectonic forces it had helped create but could not control.

The company also suffered from a chronic inability to integrate its acquisitions into a coherent product strategy. Each major acquisition — Flickr, del.icio.us, Tumblr — represented genuine potential that Yahoo couldn’t fully realize. The culture became internally focused, politically complex, and risk-averse at exactly the moment when bold experimentation was required.

By 2015, Yahoo’s core business was worth less than the company’s stake in Alibaba and Yahoo Japan — meaning the market was essentially valuing Yahoo’s operating business at a negative number. This was a devastating verdict: investors believed Yahoo itself was destroying value.

The security crises of 2013 and 2014 — when Yahoo suffered two massive data breaches affecting billions of user accounts (disclosed publicly only in 2016) — were the final blow to the company’s credibility. The breaches led Verizon to reduce its acquisition offer by $350 million and further damaged user trust.

Verizon Acquisition and the Formation of Oath/Yahoo

In July 2016, Verizon Communications announced it would acquire Yahoo’s core internet business for approximately $4.83 billion — a staggering fall from the $125 billion valuation of the dot-com peak. The deal closed in June 2017.

Verizon combined Yahoo’s assets with its earlier acquisition of AOL to form a new subsidiary called Oath, which it later rebranded as Verizon Media. The combination was premised on creating a scaled digital media business that could compete with Google and Facebook for advertising dollars. That premise never quite materialized.

In 2021, Verizon sold the majority of the Verizon Media assets — including Yahoo Finance, Yahoo Sports, Yahoo Mail, and other properties — to private equity firm Apollo Global Management for approximately $5 billion. The deal retained the Yahoo brand, which Apollo continued operating.

Meanwhile, Yahoo’s legacy stake in Alibaba had been separated into a separate entity, Altaba Inc., in 2017, which was subsequently wound down and distributed to shareholders after liquidating its Alibaba holdings. Jerry Yang had negotiated Yahoo’s initial investment in Alibaba in 2005 — a $1 billion bet that grew to be worth over $70 billion — and this investment proved to be the single greatest financial decision in Yahoo’s history.

Yahoo Today: Current Status and Ownership

Yahoo in 2025 is a fundamentally different entity from the company that defined the early web — smaller, more focused, and operating in a competitive landscape its founders could barely have imagined.

Under Apollo’s ownership, Yahoo has maintained and modestly grown its most valuable properties. Yahoo Finance remains a leading financial information platform. Yahoo Sports, particularly its fantasy sports offerings, continues to serve millions of users. Yahoo Mail, while no longer the world’s most popular email service, still has a substantial user base, particularly among older internet users for whom the address represents decades of digital identity.

The company has invested in news and sports content, sought advertising technology partnerships, and attempted to position itself as a complementary media platform rather than a comprehensive portal. It is, by most measures, a stable and profitable niche business rather than a world-defining platform.

Yahoo Japan, operating as LY Corporation after merging with Line Corporation, remains a substantial business in Japan — a reminder that Yahoo’s international legacy sometimes outlasted its American one.

The story of Yahoo is not finished. But its protagonist role in the internet’s central drama ended sometime around 2010, when it became clear that Google had won the search wars decisively, and that social media — not portals — would define the next era of online behavior.

Yahoo’s Legacy and Lasting Impact on the Internet

History will record Yahoo’s failures alongside its achievements. But the failures should not obscure how genuinely transformative Yahoo’s first decade was.

Yahoo created the template for the internet portal — the comprehensive destination that brought together email, news, search, entertainment, and community under one roof. Every major internet company that followed, from AOL to MSN to Google to Facebook, built on assumptions and user behaviors that Yahoo helped establish.

Yahoo demonstrated that the internet could be a mass-market medium — not just a tool for academics and technologists, but a daily destination for tens of millions of ordinary people. This sounds obvious now. In 1996, it was a radical proposition, and Yahoo proved it.

Yahoo Finance, Yahoo Sports, and Yahoo Mail shaped how people relate to financial information, sports data, and personal communication in the digital age. Millions of Americans still check their Yahoo Finance portfolio or Yahoo Fantasy team, habits formed in the late 1990s that have persisted across a quarter century of internet change.

The international model Yahoo pioneered — local partnerships, localized content, country-specific portals — was adopted by countless companies expanding globally. And its early investment in Alibaba, whatever the context, helped fund the rise of China’s digital economy in ways that continue to ripple through global commerce.

Perhaps most importantly, Yahoo’s cautionary tale continues to educate. Its story of complacency, missed opportunities, and strategic indecision has been studied in business schools worldwide. The lesson is not that Yahoo failed because its people were incompetent — many were brilliant. The lesson is that in technology markets, leadership advantages erode faster than in almost any other industry. The company that defines an era can be disrupted by the next era’s logic within a handful of years.

Yahoo asked “How do we hold onto what we have?” when it should have been asking “What does the internet become next?”

Conclusion: Why Yahoo Still Matters

Yahoo mattered enormously — and understanding why it eventually faded matters just as much.

It matters because Yahoo was not a fraud or a fluke. It built real products that real people loved. It created genuine value — in communication, in information access, in community — that shaped how hundreds of millions of people first experienced the internet. Those experiences formed habits, expectations, and intuitions about what the digital world could be. Without Yahoo’s decade of dominance, the internet’s second act would have looked very different.

It matters because Yahoo’s failure teaches us something about the nature of innovation itself. Disruption rarely comes from where incumbents expect it. Yahoo watched Google rise and believed, for too long, that search was just a feature rather than a platform. It watched social media emerge and couldn’t move quickly enough to participate meaningfully. The greatest danger for any dominant technology company is not competitors who are obviously better — it’s competitors who are differently better, who see the world through a different frame.

It matters because Yahoo’s cultural artifacts — the yodel, the purple logo, the early-morning homepage habit, the Yahoo Mail address that served as your first internet identity — are part of the shared memory of an entire generation’s encounter with the digital world. That’s not nothing. That’s history.

For tech companies today, Yahoo’s greatest lesson may be the hardest one: being first is an advantage, but it is not a destiny. The internet rewards those who keep asking what comes next. Yahoo stopped asking too soon.

In the long arc of internet history, Yahoo deserves its place of honor — as the company that first convinced the world the web was worth exploring, and as a reminder that even the most powerful platforms must keep evolving or cede the future to those who will.

Key Timeline Summary

| Year | Event |

|---|---|

| 1994 | Jerry Yang and David Filo create “Jerry and David’s Guide to the World Wide Web” at Stanford |

| 1995 | Yahoo incorporates; Sequoia Capital invests $2 million; Tim Koogle hired as CEO |

| 1996 | Yahoo IPO at $13/share; Yahoo Japan launches with SoftBank |

| 1997 | Yahoo acquires RocketMail, relaunches as Yahoo Mail |

| 1998 | Yahoo passes on acquiring Google’s technology for ~$1 million |

| 1999 | Yahoo acquires GeoCities for $3.57 billion and Broadcast.com for $5.7 billion; stock peaks at $125B market cap |

| 2000 | Dot-com crash; Yahoo stock falls 97% from peak |

| 2002 | Yahoo acquires Inktomi; passes on Google acquisition at $3 billion |

| 2003 | Yahoo acquires Overture Services (paid search pioneer) for $1.63 billion |

| 2004 | Yahoo launches its own search engine; Google IPO surpasses Yahoo’s valuation |

| 2005 | Yahoo acquires Flickr; invests $1 billion in Alibaba |

| 2006 | Yahoo passes on acquiring Facebook for $1 billion; passes on YouTube |

| 2007 | Jerry Yang returns as CEO |

| 2008 | Yahoo rejects Microsoft’s $44.6 billion acquisition offer |

| 2009 | Yahoo–Microsoft search deal signed; GeoCities shut down |

| 2012 | Marissa Mayer appointed CEO |

| 2013 | Yahoo acquires Tumblr for $1.1 billion; suffers massive data breach (disclosed 2016) |

| 2016 | Verizon announces acquisition of Yahoo’s core business for $4.83 billion |

| 2017 | Verizon deal closes; Oath subsidiary formed |

| 2019 | Tumblr sold to Automattic for ~$3 million |

| 2021 | Apollo Global Management acquires Yahoo from Verizon for ~$5 billion; Yahoo Answers shut down |

| 2025 | Yahoo continues operating under Apollo, with Yahoo Finance, Sports, and Mail as flagship properties |

FAQ about Yahoo

Who founded Yahoo and when?

Yahoo was founded by Jerry Yang and David Filo, two Stanford University electrical engineering Ph.D. students, in January 1994. It was incorporated as a company in March 1995 and went public in April 1996.

Why did Yahoo fail to compete with Google?

Yahoo failed primarily because it prioritized building a comprehensive portal over investing in search quality. While Yahoo’s search product was adequate, Google’s superior algorithm, cleaner user experience, and more effective advertising model consistently outperformed it. Yahoo also missed multiple opportunities to acquire Google early, and by the time it mounted a serious search challenge in 2004, Google had too great a head start.

What was Yahoo’s most successful product?

Yahoo Finance is arguably Yahoo’s most enduring and successful product. Launched in 1997, it remains one of the most visited financial information platforms in the world as of 2025, even after multiple ownership changes. Yahoo Mail and Yahoo Sports Fantasy also maintained significant user bases across decades.

Who owns Yahoo today?

As of 2025, Yahoo’s core internet properties — including Yahoo Finance, Yahoo Mail, Yahoo Sports, and Yahoo News — are owned by Apollo Global Management, which acquired them from Verizon Communications in 2021 for approximately $5 billion.

What was Yahoo’s biggest missed opportunity?

Most analysts point to two equally significant missed opportunities: declining to acquire Google in 2002 for $3 billion (when Google later became worth trillions), and rejecting Microsoft’s $44.6 billion acquisition offer in 2008 under Jerry Yang’s leadership. The Microsoft rejection particularly cost shareholders as Yahoo’s value subsequently declined dramatically.

So, this was the BigStory of Yahoo, the company that once defined how the world experienced the internet. At BigStories, our goal is to revisit the moments, decisions, and innovations that shaped the digital world we use every day. Did you enjoy reading it? If this story brought back memories or helped you discover something new, consider sharing it with others who remember the early web, and continue exploring more BigStories that uncover the origins of the modern internet.